What is lung cancer?

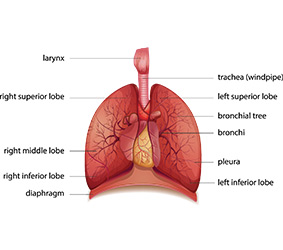

The lungs are the “bellows” that enable us to take in oxygen from the air and expel carbon dioxide waste from our body.

The lungs are the “bellows” that enable us to take in oxygen from the air and expel carbon dioxide waste from our body.

Lung cancer is a cancer of the cells of the lungs. When cells become old or damaged, the body will replace them with new cells. Usually, the process of cell division and replacement occurs in a controlled manner. When cells become cancerous or malignant, however, damage to the DNA (the genetic instructions inside each cell) cause them to look and behave differently from normal cells. Cancer cells reproduce uncontrollably and start to invade nearby tissue or even travel to other parts of the body (a process known as metastasis). This abnormal growth can interfere with the normal functioning of the lungs.

There are two main types of lung cancer: non-small cell lung cancer (which accounts for about 85% to 90% of all cases) and small cell lung cancer. A form of cancer called pleural mesothelioma affects the lining of the lungs (the pleura). This form is very different from lung cancer and is usually caused by inhaling asbestos.

Overall, lung cancer is the second most common cancer diagnosed in Ontario, following breast cancer.

Overall, lung cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in Ontario, following breast cancer. Among males, it is second only to prostate cancer; in females, it is second only to breast cancer. A man’s lifetime probability of developing lung cancer is 1 in 17, and a woman’s is 1 in 18. The risk increases with age. For both males and females, lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death.

Risk factors you can change or control

Smoking

Smoking increases the risk of lung cancer nine-fold, with some studies reporting the risk to be up to 20-fold greater. The more you smoke and the longer you smoke, the greater the risk. Cigars are not a safer alternative and also increase the risk of lung cancer.

Smoking is responsible for 71% of all cases of lung cancer in Ontario. Although the incidence and mortality rates of lung cancer have declined in men, in women they increased during the 1980s and 1990s, until levelling off in the late 1990s. These changes probably reflect the fact that over the past several decades smoking rates declined faster among men than women. At the same time, it is important to know that even people who don’t smoke can develop lung cancer.

Tobacco smoke is dangerous because it damages the cells of the lungs and can cause mutations in cell DNA. Some of the chemicals in tobacco smoke also interfere with genes that help the body suppress the growth of tumours and get rid of damaged cells.

When you quit smoking, the lungs begin to repair themselves. The risk of lung cancer begins to fall within 2 to 5 years after quitting. Within 10 years, the risk of lung cancer falls by about half (between 30% and 50%). Former smokers who quit more than 20 years ago have the same risk of lung cancer as someone who has never smoked. The earlier in life a person stops smoking and the longer the person is smoke-free, the greater the reduction in risk.

Second-hand smoke

Being around someone who is smoking (referred to as second-hand smoke or passive smoking) exposes you to the carcinogenic chemicals in tobacco smoke. Living with a smoker or being exposed to second hand smoke at work can increase a non-smoker’s risk of lung cancer by 20% to 40%. The longer a person is exposed to second-hand smoke, the greater the risk. There is evidence suggesting that being exposed to second-hand smoke as a child may increase the risk of lung cancer in adulthood.

Environmental or occupation exposures

-

Living in or near a large city

Living in or near a large city for at least ten years exposes you to airborne emissions from vehicle exhaust, industrial plants and residential heating. These emissions release fine and ultrafine particulate matter into the air. When you inhale this particulate matter, it can settle deep in the lungs and damage the respiratory system – increasing the risk of lung cancer. The risk is highest for people who live near major highways and roads.

-

Asbestos

Asbestos refers to a group of six fibrous minerals that are found in some rocks and soil. Because they are resistant to heat, in the past asbestos was used for a wide range of industrial applications and consumer products. Occupational exposure to asbestos fibres may occur during the weathering or mining of natural asbestos deposits or products, or disturbance of asbestos-containing materials during use, demolition work, or building, home repair or remodeling. When asbestos is disturbed or damaged, fibres can be released into the air. If inhaled, these fibres lodge in the lungs, causing damage and inflammation that increases the risk of lung cancer. People who are exposed to asbestos will have an even greater risk of lung cancer if they also smoke.

Talk to your supervisor, health and safety specialist, industrial hygienist and/or local union representative about asbestos exposure in your workplace. Some questions to ask are:

- Is asbestos addressed in health and safety training?

- Has any air monitoring been done? If so, how did the results compare to the occupational exposure limits for asbestos?

- What has been done to control for asbestos exposure?

- Have all potential sources of asbestos been marked and labeled?

It’s important to talk with your supervisor, health and safety specialist, industrial hygienist, and/or local union representative if you think you may be exposed to any of the following substances or processes in your workplace. Health and safety measures, including workplace controls and personal protective equipment, should be used by both your employer and you to limit your exposure.

-

Arsenic and inorganic arsenic compounds

Arsenic was used in the past and is still used commercially in several industrial processes, such as the making of some metals, pharmaceuticals, wood preservatives, agricultural chemicals and pesticides, as well as in the production of alloys, glass-making, and in the mining and smelting industries. Another potential source of occupational exposure to arsenic is burning fossil fuels such as coal or gas. Occupational exposure to arsenic can significantly increase the risk of lung cancer. There is also some evidence showing that smokers may be more sensitive to the damaging effects of arsenic.

-

Diesel engine exhaust

The exhaust from diesel engines contains a complex mixture of fine diesel particulate matter (DPM) small enough to be inhaled deep into the lungs. These particulates can damage the lungs and increase the risk of lung cancer. People who are frequently exposed to diesel engine exhaust, such as underground miners, truckers, railway workers, heavy equipment mechanics and construction workers (among others), have an increased risk of lung cancer. The risk increases with the amount of exposure.

-

Radon

Radon is a colourless, odourless radioactive gas that occurs naturally in the environment when uranium and other radioactive substances decay. The radon levels in the environment vary between different parts of the country – or even in different parts of the same region or from building to building. Depending on the geographic location, people who work in underground mines, subways, tunnels, construction exaction sites, or basements may be exposed to radon. If radon is present and a building or site is not well ventilated, radon gas can accumulate. If radon gas is inhaled, it can increase the risk of damage to the lungs and of lung cancer. Studies have consistently shown that people exposed to radon who also smoke have an even greater risk of lung cancer.

-

Silica dust and crystalline silica

Silica and crystalline silica are naturally occurring components of some rocks, sand, granite, some clays and other minerals. Common forms of crystalline silica include quartz and cristobalite. Sand and gravel are used in manufacturing glass and ceramics and are used in foundries. Quartz crystals are used in the making of jewellery, electronics and optical equipment. Another form of silica, diatomaceous earth, is used as a filler in pesticides, cleaners and other products. Occupational exposure to silica dust and crystalline silica may occur among miners, farmers, those who are involved in the demolition of concrete, abrasive blasting, stone cutting, quarry work and those who work in industries where silica is used. When silica particles are inhaled, they settle deep in the lung. Chronic exposure to silica dust and crystalline silica can interfere with the lungs’ ability to clear away debris and cause persistent inflammation. This can increase the risk of lung cancer.

-

Nickel compounds

Nickel is a hard metal found in many ores used in the mining, milling and smelting industries. Exposure to nickel compounds can occur in the manufacturing of metal alloys, steelmaking, metal plating and electroforming plants, nickel refineries, petroleum refineries, fats and oils hydrogenation plants, coal gasification and battery production plants. People who are exposed to nickel at work have an increased risk of lung cancer compared to people who are not exposed.

-

Beryllium and beryllium compounds

Beryllium is a metal that occurs naturally in some rocks, coal, oil, soil and volcanic dust. It’s used in the manufacture of metal alloys, such as those used in making airplanes, cars and trucks, computer and photography equipment, sports equipment and a number of consumer products, including dental bridges. Occupational exposure to airborne beryllium compounds and beryllium dust is the most common route of human exposure and can occur in the energy, electrical, defense and fire prevention industries. Workers in beryllium processing plants have been observed to have an increased risk of lung cancer. The risk increases with the length and intensity of the exposure.

-

Cadmium and cadmium compounds

Cadmium is a soft metal used in the production of pigments and nickel-cadmium batteries and in the metal-plating and plastics industries. Occupational exposure to cadmium can also occur at zinc, lead or copper smelters. One of the most common sources of exposure to cadmium for most people is cigarette smoke: cadmium is among the many chemicals released in cigarette smoke. People who are exposed to cadmium at work have a significantly increased risk of lung cancer.

-

Chromium (VI) compounds

Chromium is a metal that naturally occurs in rocks, animals, plants and soils. There are several types of chromium. Chromium (VI) or hexavalent chromium is present during chrome plating, the production of ferrochrome (a chromium and iron alloy) and the manufacture of textile dyes, paints, inks, toners for copying machines, pigments, wood and leather preservatives, plastics, and corrosion inhibitors. It is also used in the treatment of cooling tower water and drilling muds. Other industries where occupational exposure to chromium (VI) can occur include ore refining, stainless-steel production, the production of some chemicals and substances used in high-temperature processes (refractory production), cement-producing plants, and the manufacture of automobile brake lining and catalytic converters. Even when you control for smoking, people who are exposed to high levels of chromium (VI) have an increased risk of lung cancer.

-

X-ray and gamma-radiation

Depending on how much radiation a person is exposed to, X-ray and gamma-radiation may damage the lungs and increase the risk of lung cancer. People who work close to sources of X-ray or gamma-radiation may be exposed to radiation for prolonged periods of time.

-

Occupational exposures by industry

If you work in certain industries, you may be exposed to metals, dust, fibres, gases or other compounds that may increase the risk of lung cancer. Within each industry, the amount of carcinogenic chemicals released varies according to the type of process used and what safety controls are in place to minimize exposure. Exposure to cancer-causing substances can also vary according to how close you work to these substances, how long you’ve worked there and whether you’ve been using protective clothing and devices such as respirators and gloves.

You can’t change where you’ve worked in the past or possibly even where you work in the future. But you may be able to help reduce your risk by using the right protective equipment and making other healthy choices.

-

Painting

The chemicals in paints and stains vary for different paint formulations. Exposure can also vary between different painting occupations (e.g., construction painters, artistic painters and consumer production painters). Painters and those who work in places where paints or dyes are manufactured may breathe in or have skin contact with cancer-causing substances such as arsenic, cadmium, chromium (VI), nickel and silica. The risk is higher if you don’t use protective equipment such as respirators and gloves.

-

Iron or steel founding

Iron and steel foundries can use different processes and materials that expose workers to a wide variety of chemicals, metals, dust and gasses. Some of the most concerning substances include silica dust, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and airborne chromium and nickel compounds. The risk of lung cancer increases with your level of exposure and how long you’ve worked in the industry.

-

Rubber manufacturing

Workers in the rubber manufacturing industry are exposed to dust and other emissions during the making, handling, milling, extruding, curing and assembling of natural and synthetic rubber products. The exact chemicals used have changed over time and depend upon the factory’s equipment and the type of product being made. Chronic exposure to some of the emissions generated during the rubber-making process may increase the risk of lung cancer.

-

Coke ovens

Coke is coal that has been carbonized for use in iron-making blast furnaces and other metal-smelting industries. Those who work around coke ovens are exposed to emissions that contain substances associated with an increased risk of lung cancer. Some of these substances are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and vapours (volatiles) from coal tar (a sludgy by-product when coal is burned to make coke or gasified to make coal gas) or coal tar pitch (the residue produced by the distillation or heat treatment of coal tar). People who work around coke ovens may also be exposed to other compounds such as asbestos, silica, arsenic, cadmium and nickel.

-

Coal gasification

The process of turning coal into alternate forms of energy (e.g., synthetic natural gas) releases emissions that contain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), arsenic, asbestos, silica, cadmium, nickel and other chemicals. People who work in coal gasification plants have an increased risk of lung cancer.

-

Aluminum smelting

People who work in factories where electrolytic processes are used to produce aluminum may be exposed to emissions that contain cancer-causing substances such as coal tar, coal tar pitch vapours (volatiles), or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Prolonged exposure could increase the risk of lung cancer.

-

Risk factors you can’t change or control

Family history

To date, no specific gene has been found for lung cancer. At the same time, there is some evidence that having a first-degree “blood” relative (mother, father, brother, sister, or child) with lung cancer is associated with an increased risk. Some of this risk may be due to shared behaviours such as smoking or being exposed to second-hand smoke. Researchers are still working to determine if a genetic mutation for lung cancer can be inherited.

What you can do to protect yourself

Be smoke-free

The single most important thing you can do to reduce your risk of lung cancer is to be smoke-free: avoid smoking any tobacco product (cigarettes and cigars) and exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke.

When someone quits smoking, there are immediate benefits such as:

- Improved sense of taste and smell.

- Within weeks, lung capacity begins to improve as damaged cells are replaced.

- Decreased coughing, sinus congestion and shortness of breath.

Within a few years of quitting, a smoker’s risk of lung cancer begins to fall. The risk of other diseases, such as heart disease, also begins to fall. The younger people are when they quit and the longer they remain smoke free, the lower the risk of lung cancer.

Tips if you’re a smoker who is ready to quit

- As a smoker, you’ve probably heard that quitting is one of the best things you can do for your health. Don’t worry if you’ve tried to quit before and have relapsed. It can take some people up to six times before they are successful in staying smoke-free. Each attempt you make will bring you closer to your goal of being smoke-free and healthier.

- Even before you’re ready to quit, you can start to gain control by delaying and distracting. Delay having your next cigarette by five or ten minutes by distracting yourself with something else. Over time, you’ll probably find that you gain more and more control and can delay that cigarette longer and longer. Congratulations — you are on your way to controlling your smoking, rather than having smoking control you.

- Planning is the key to success. Develop a plan for how you will quit (cutting down, cold turkey, or using a smoking cessation aid), when you will start (your quit date), and who will help you and be your quit smoking buddy or coach. Your quit smoking buddy or coach should be someone who will be sympathetic but firm to help you stay on track.

- Write out your reasons for quitting and post it someplace where you will see it regularly. Everyone has his or her own reasons to quit. It may be something like:

- I want to feel better.

- I don’t want to die and leave my family.

- I’m a smart person but cigarettes make me look dumb.

- I don’t want to pollute the air my family breaths.

- I’m tired of being out-of-breath.

- I don’t want to smell like an ashtray any longer.

- When developing your quit smoking plan, explore all of your options. Don’t be afraid to ask for help. Six out of ten smokers use a smoking cessation aid. Talk with your doctor, nurse practitioner or pharmacist about nicotine replacement therapy, medications or cessation programs.

- Get the support of others by joining a smoking cessation program or support group. Your local public health unit can connect you with smoking cessation programs in your community. There are also online groups and blogs in which quitters exchange ideas and help one another.

- Most smokers find that particular places or activities trigger them to automatically light up. Sit down with a piece of paper and write down your smoking triggers. Then try to think of what you can do to avoid these places or activities. For example, if you always have a cigarette with your morning coffee, switching to tea or drinking your coffee later in the day may disrupt the habit.

Tips if you’re a smoker but not ready to quit

- Write down or think about how you would feel if you could quit. For example, would you feel better about yourself and more in control of your life? Would it make you a better role model for your children or loved ones? Would it give you a better chance of living to enjoy a healthy retirement? Think about what your life would be like if you could quit.

- Keep track of your smoking. Sometimes, just seeing how much they are smoking — and being more aware of when they are reaching for a cigarette — can help people to cut back. Keep a count of every cigarette you smoke on your cell phone, a piece of paper or your computer.

- Book an appointment with your doctor or nurse practitioner or talk with your pharmacist about smoking cessation aids and programs that might make it easier for you to quit. Investigate all your options so you can think about what you may do in the future.

- Remember that everyone can change. Just because you are a smoker today doesn’t mean you have to be one tomorrow. Millions of Canadians — including people who smoked for decades — have quit. Every time you try to quit, you are moving closer to the goal of being permanently smoke-free.

Tips to avoid second-hand smoke

Non-smokers who are regularly exposed to second-hand smoke may be at increased risk of lung cancer. To keep your risk as low as possible, try to avoid second-hand smoke as much as possible.

- Think of when and where you are exposed to second-hand smoke. Is it at home, in the car or in public places? Once you have identified where and when this is happening, try to think of ways you can change the situation. Could you ban smoking from your home or car?

- Asking friends and family to not smoke in your presence can be difficult. But remember: you are doing this to protect your health. Explain the effect that their smoke can have on your health.

- Focus on your long-term goal: a long and healthy life with the people you love.

Learn more about how to become and stay tobacco-free or how you can help someone you care about to quit:

- Speak to a Care Coach at Health811 for quit smoking support by calling 811, TTY 1-866-797-0007.

- Visit Smokers’ Helpline to connect with an online group of other quitters, Quit Coaches, and additional resources. You can also text iQuit to the number 123456 (in Ontario) for quit support.

- The Ontario Ministry of Health’s Quit Smoking website.

- Health Canada’s On the Road to Quitting program.

- Find out how much your habit is costing you with the Healthy Canadians Cost Calculator.

- Visit QuitMap.ca to find a quit smoking counsellor or group in your community.

- Make Your Home and Car Smoke-Free.

- Visit the Indigenous Tobacco Program website to access resources for First Nations, Inuit, Métis and urban Indigenous peoples.

Protect yourself at work

You can’t change where you worked in the past or maybe even where you’ll work in the future. To protect yourself, talk to your supervisor, health or safety specialist, industrial hygienist, or local union representative about exposures in your workplace. Ask:

- Has air monitoring been conducted in your workplace and what are their levels compared to the occupational exposure limits?

- If there is potential for airborne exposure for cancer-causing substances at work?

- What has been done to control or limit your exposure?

Employers and employees have responsibilities for controlling and reducing exposure in the workplace. Your employer is responsible for putting in place engineering controls and administrative controls (e.g. using less hazardous alternatives, ventilation, enclosures, reducing time in exposed work situations) and providing training and personal protective equipment to employees where needed.

Employees can take action to protect themselves. Things that you, as an employee, can do include:

- Being aware of the hazardous materials used in your workplace.

- Observing the health and safety regulations provided by your employer.

- As much as possible, working away from the source of exposure and minimizing the amount of time you handle the material.

- Using the right protective equipment such as respirators, protective clothing, gloves, boots, or face shields.

- Practicing safe work practices like using local exhaust ventilation and partial enclosures where feasible.

- Avoiding eating or drinking in places where there are gases, fumes or dust.

- Maintaining good hygiene and housekeeping practices, such as keeping surfaces at the workspace clean, skin decontamination at breaks and at the end of work, and washing your work clothes regularly.

- Using disposable or reusable work clothes that stay at the work site so you don’t bring them home.

Even if you don’t have any symptoms of lung cancer, such as coughing or difficulty breathing, tell your doctor or nurse practitioner about your workplace exposure. This is important information for your doctor or nurse practitioner to know.

Learn More:

- To learn more about known or suspected carcinogens Canadians may be exposed to at work, visit the CAREX Canada website.

- To ask questions, go to the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety or call 1-800-668-4284.

- Learn about workplace health and safety standards at the Ontario Ministry of Labour or call the Ministry of Labour Health & Safety Contact Centre at 1-877-202-0008 (TTY 1-855-653-9260).

Find out about radon

Levels of radon differ across the province. Even in the same area, radon levels can vary from house to house and at different times of the year. If you are concerned about radon levels in your home or building or radon has been detected, Health Canada has recommendations to guide you.

Learn More:

Reduce your risk from air pollution

If you live in a major city, check your local air quality index regularly and plan your activities accordingly. On days when the air quality is poor, you may want to avoid doing strenuous activities outdoors, especially in high-traffic areas.

Learn more:

- Visit Air Quality Ontario.

- To hear a recording of Air Quality readings and forecasts dial 1-800-387-7768 (416-246-0411 in Toronto) for information in English or 1-800-221-8852 for information in French.

- To find out more about road traffic and air pollution.